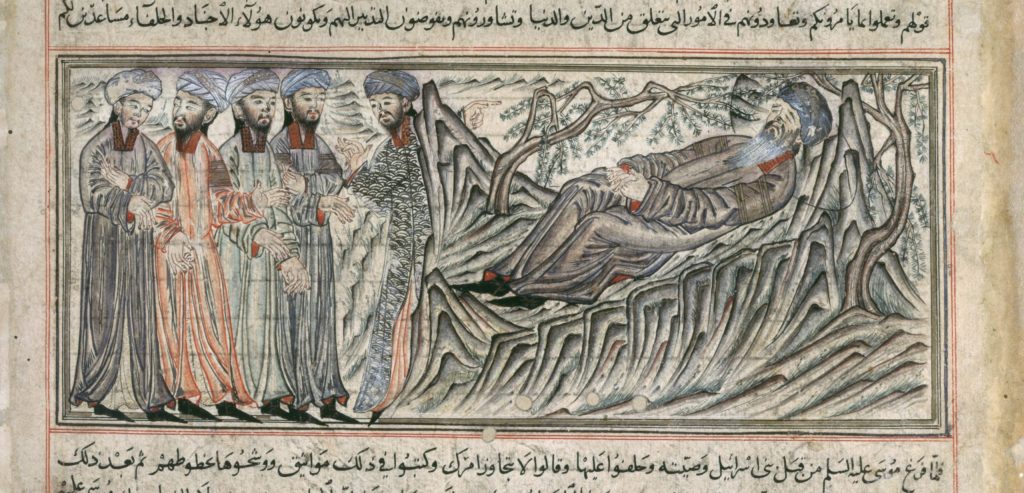

In the bustling intellectual hub of 14th-century Tabriz, a remarkable manuscript emerged that would challenge our modern notions of religious and cultural boundaries. The Jami’ al-Tawarikh, or “Compendium of Chronicles,” stands as a testament to the rich tapestry of interfaith dialogue and collaboration that once flourished in the medieval Islamic world.

At the heart of this story is Rashid al-Din Fadlallah, a man whose life embodied the cultural crossroads of his time. Born into a Jewish family in Hamadan, Rashid al-Din converted to Islam and rose to become a powerful vizier in the Mongol Ilkhanid court. His diverse background and insatiable curiosity drove him to create one of the most ambitious historical works of the medieval era.

His diverse background and insatiable curiosity drove him to create one of the most ambitious historical works of the medieval era.

The Jami’ al-Tawarikh was no ordinary chronicle. Commissioned by the Mongol rulers Ghazan and Öljeytü, it aimed to compile a comprehensive history of all peoples the Mongols had encountered. This monumental task required a level of cultural understanding and interfaith cooperation rarely seen before or since.

Imagine a scriptorium where scholars pored over texts in Latin, Arabic, Persian, Syriac, Mongolian, Chinese, and Sanskrit. Picture artists studying Christian Gospels, Jewish Old Testaments, and Chinese handscrolls to create illustrations that would resonate across cultural boundaries. This was the reality of the Rab’-i Rashidi, Rashid al-Din’s grand complex in Tabriz where the Jami’ al-Tawarikh took shape.

The manuscript’s illustrations are a visual feast of cultural fusion. In depicting scenes from the life of the Prophet Muhammad, artists ingeniously adapted Christian iconography, creating a unique visual language that bridged Islamic and Christian traditions. Chinese motifs dance alongside Byzantine-inspired figures, while silver detailing (now oxidized) adds a touch of luxury that transcends cultural boundaries.

But the Jami’ al-Tawarikh is more than just a beautiful book. It represents a worldview where knowledge knew no borders, where the histories of Arabs, Jews, Mongols, Franks, Indians and Chinese were seen as equally worthy of preservation and study. In an age often characterized by conflict, this manuscript stands as a beacon of intellectual openness and cross-cultural appreciation.

In an age often characterized by conflict, this manuscript stands as a beacon of intellectual openness and cross-cultural appreciation.

The story of the Jami’ al-Tawarikh challenges us to reconsider our assumptions about medieval interfaith relations. It reminds us that there were times and places where curiosity and scholarship trumped division, where the sharing of knowledge was seen as a noble pursuit regardless of its source.

As we marvel at this extraordinary artifact, we’re invited to reflect on our own times. In an era where cultural misunderstandings often lead to conflict, what can we learn from the spirit of collaboration that produced the Jami’ al-Tawarikh? How might we foster similar exchanges of ideas and artistic inspiration across the religious and cultural divides of our own world?

The Jami’ al-Tawarikh stands not just as a historical treasure, but as an inspiration for our future. It challenges us to look beyond our differences, to seek out the common threads of human experience, and to create works that celebrate the rich diversity of our global heritage. In doing so, we might just find that the spirit of Tabriz’s medieval scriptorium has much to teach our modern world about the power of interfaith dialogue and collaboration.